Headless Holidays

Juju Noda’s Mini Doc - Frame grab from a driving sequence

Good composition is deeply subjective. Despite all the formulas, rules and framing guides we’re taught, I have always felt composition is more instinct than instruction. Some people have it, and — controversial as it may sound — some don’t. My dad for example, he couldn’t frame a picture to save his life - considerable amounts headless holiday memories.

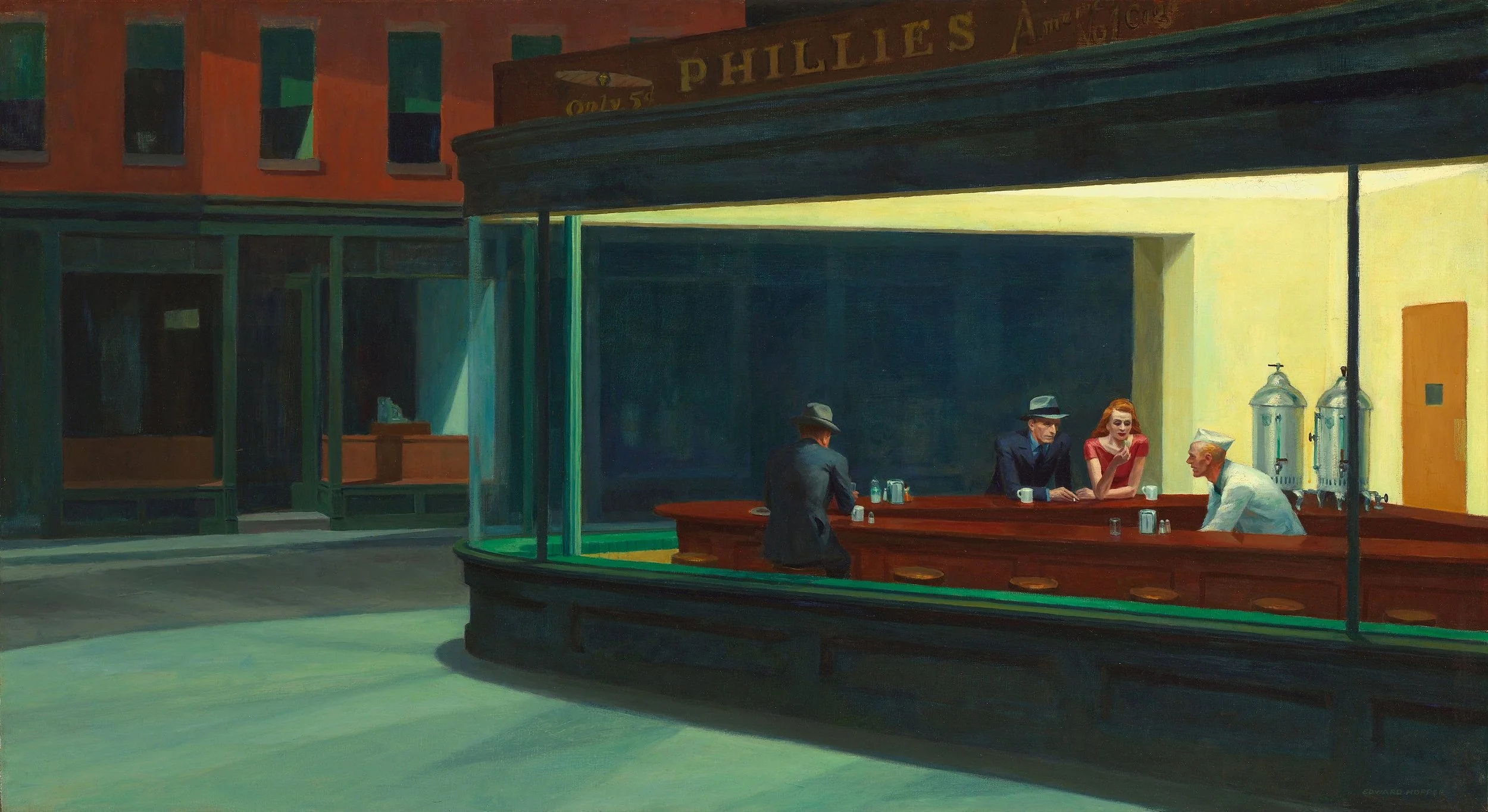

But that said, it’s not magic. It’s might start with an instinct but it’s a skill which can be developed. Some of the best teaching tools are the films, painting and photographs we have around us, the stuff that inspires us. I love Edward Hopper, Nighthawks especially, a painting which I have been lucky to view in person.

Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942

So when it comes to collaborating on a project, it’s essential that everyone shares the same compositional instincts — or at the very least, understands the logic behind the visual language being used. A and B camera should feel like an extension of the same eye, not an alternative. Operators generally need to be in sync with the DP and directors vision. The frame shouldn’t feel like two windows into the same world… unless it’s suppose to.

To me, composition isn’t about creating something that looks "cinematic", or wedging a chair into the corner of frame for balance. It’s about what a shot is doing — emotionally, narratively, structurally. What’s the composition doing for the shot before and after it? What’s being revealed and what’s withheld?

These decisions often start early — in pre-production, recces, or more regrettably the morning of a job. Shot size, lens choice, camera height… they all influence how the audience interprets a moment. I use Cadrage, a viewfinder app, to sketch out options quickly. It lets me load in my camera and lens package, visualise real compositions with approximate focal lengths, and share them easily with directors, producers or crew. It’s fast, lightweight and practical — like a director’s viewfinder that can share a shows visual language, and help everyone else understand that language too.

Cadrage Photo-board for a recent Nike commercial, directed by featured James Copson

I’m a huge a fan of the EVF — in my case, a DVF-EL200. It’s old school in the best sense. It cuts out the noise. There’s no distraction, no colour shift or glare from a sun-blasted monitor, just the frame and what’s in it. Paddy Blake, an ACO member and operator I really respect, swears by a monitor. We chatted about this at an ARRI course recently. At the end of the day, it’s whatever keeps you connected. I use both, but for me, the EVF gives me a chance to think and breath — literally and mentally.

ACO Course at Arri Rental

Lens choice plays a huge role in that framing conversation. I tend to prefer primes. They impose a creative discipline — a set of self-imposed limitations that force clarity. You can’t punch in but you can move. You can reframe. And you do commit. That commitment helps me stay honest to the tone and language we’ve established for the project. I’m either close to the subject, or I’m not. And if I’m not, I’d better have a reason. There’s no pretending to be intimate with a 200mm from the end of the street. Actors feel that distance. So does the audience.

That said, despite my love of primes I’ve been using the DZOFILM Catta Ace zooms quite a bit — especially on documentary work and branded content where speed matters. They’re light, sharp without being clinical, and I’ve just had the telephoto 70–135mm serviced, which made it feel brand new again. The focus fall-off is lovely, especially wide open, and they’ve never let me down. But for drama, commercial or more considered work, I default to primes. Not out of snobbery, but to build rhythm — a visual grammar that holds up for the entire piece.

While on the topic of lenses, I don’t obsess over resolution or razor-sharp optics. I care about how the lens sees. Its fall-off, the behaviour at the edge of frame, the micro-contrast. A lens shouldn’t just describe the scene — it should translate it. When I say how the lens “sees”, I mean how it makes me feel when looking through it.

DZO Catta Ace Zoom lens, Sony Venice

For most DPs, lens choice is more emotional before it's technical. A 40mm from on a close-up from 3ft feels different to a 135mm from 8ft, even if the shot size looks the same. That emotional relationship between subject, lens and background is a core part of how I try to shoot. With docs especially it’s about perfection — it’s presence and intention.

I think the best operators don’t always strive for beauty, they balance the geometry with meaning, which further includes movement and shot development. To me at least, great composition is about tension and release. A wide shot isn’t just a wide — it can be a release of energy, a moment of isolation or a beat of stillness. A close-up isn’t just coverage — it’s intimacy, or pressure or claustrophobia or a simple nod to the audience that this thing is important. These aren’t automatic aesthetic decisions — they’re emotional ones based on the story being told. For example, the over-the-shoulder. These shots anchor a conversation, provide geography and help position characters in space. Compositionally I tend to prefer singles. A single puts the audience right into the emotional perspective of a character. It strips away the visual noise — no back of head, no silhouette shoulder — just performance and psychology. But I’ll use an OTS when I want to connect characters, to physically place them in relation to one another or to highlight tension or distance.

Everything in the frame either helps the story, or it distracts from it. So whether I’m framing up a hurried corporate at Lloyds of London, rehearsing blocking with a director on a short narrative or buried in the EVF on a documentary job, I try to keep asking… What is this shot doing? For the story, for the scene, for the film and for the audience?

Because if the shot isn’t doing something — it’s probably not worth doing at all - well unless its a holiday photo taken by my old man, in thats case head or no head, I love it.